Why Snow is Good (mostly), and The Art of Driveway Maintenance

Acording to reputable measurements, fifty three inches of snow have fallen – so far – on our corner of the Hudson Valley. Fine with me, especially because I’m not the one shoveling (see below). But also fine with the gardens, safely insulated beneath a protective blanket that keeps roots from heaving, shelters essential microorganisms, and helps prevent excessive breakdown of nutrients.

None of this is news to long time plant people, but even as a very long time plant person I was amazed at the extent to which snow matters in the larger environment. If you wish to be amazed too, check out Colder Soils in a Warmer World: Snow Depth, Soil Freezing and Nitrogen losses in the Northern Hardwood Forest. We learned about it at Snow is Good, a lecture given by Dr. Peter Groffman (last Friday, at Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies), a lecture we were only able to attend because Bill thinks snow shoveling is good.

On shoveling snow: physics, efficiency, work and art.

It is beautiful, as Leslie says, the soft whiteness of snow, the purity reducing all forms and structures to their most monochromatic essence. “Yes, agreed,” I say, and quietly open the door and pick up the shovel. But the novelty of this white on white world quickly disappears from my thoughts and view.

I hoist the shovel, put leg and back to the task ahead and invariably sink into the repetitive task and thoughts which come back as regularly as breaths, each pass of the shovel, push of the legs, flex of the back, hips, arms. I fall into the trance of physical labor and recall lessons of my teachers.

It was Mr. Lowery, my High School agriculture, physics, and shop teacher who years ago gave the lesson of the inclined plane, that most efficient of tools. His examples were of the screw, the driver and plow. But now with the task at hand they seem to me to be most elegantly expressed in the snow shovel, with its blade gradually inclined into a curve, a graceful turning into itself which gathers and compresses the loose and light snowflakes into a more and more compressed and manageable mass.

I think also of inertia, the laws of bodies in motion, as the mass of my 150 pounds moves easily at a steady pace toward the end of the pass. No need to tell myself it is more work to stop and restart midway than to keep going. Every muscle in my body has personal experience with this simple truth. A body in motion tends to stay in motion. My grandmother taught me this. Stop and you are dead she once told me. And so I push through to the end of this, the first of many such passes.

That first pass is important and requires some consideration for all others will follow and build upon its placement.

The snow may be light and fluffy now, but given the way it soaks up ambient moisture from air and soil, it soon will become heavy. With the daily rise and fall in temperature it becomes increasingly immobile. Better to do too much than too little, said my Mother and her brother, echoing the lessons from their immigrant parents. I tell this to my neighbors who have never had to deal with shoveling snow.

The difference is expressed in being boxed in by mounds of ice or having room to maneuver. Do a little more than necessary and where ever possible let nature, in this case the sun, help you.

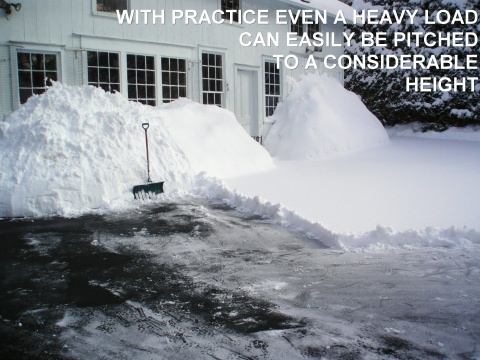

At the end of each pass comes the task of lifting and with it the lessons of countless lifts and throws in my life. Skipping flat stones over the surface of a pond, counting the number of skips before the stone sinks. Throwing a baseball into the glove of a catcher or bales of hay onto the truck or into the loft. In each case one leg being worth at least two arms. In each case the inertial energy of the body’s mass redirecting and focusing that energy by a series of internal fulcrums to a specific point, the body moving gracefully through a series of curves not unlike the inclined plane of the screw, shovel, or plow.

The physics of lifting described: At the end of the pass I bend my knees, left leg forward pushing into the snow. As the knees bend, the left hand comes forward on the handle of the shovel and only then tightens its grip. With a single smooth motion I stand and the shovel with its load of snow comes up with my body, the legs doing almost all of the work.

Continuing the movement I step backwards and the shovel with its load of snow now falls downward, pulled by gravity, increasing in speed. Without a pause I shift my weight from the left to the right leg, then to the repositioned left, swinging the shovel at first downward then upward as I redirect the fall, moving this mass of snow perhaps ten or fifteen feet.

Towards the end of the lift the left hand loosens the grip while the right hand, holding the end of the handle, directs the load to where I want to place it and abruptly stops. The load slides off the shovel, continues its trajectory, and lands as easy as a cat just where it is meant to go.

All of this is easier done than said. Words, after all, mediate reality; they point to and arrest the dynamic process. In this sense, as every good quarterback comes to know, the discursive, denotative nature of language can impede or get in the way of the process itself. I once, and only once, took a Tai Chi lesson. The instructor looked amazed. “How did you learn these movements?” he asked. “Pitching hay and ice skating” I replied. “Ahh, yes”, he exhaled with a nod, a smile and a wink. I saw no need to come back.

There is something artful about physical labor, especially with those tasks which require repetition. Not only does it become mindless, but the work becomes emotionless as well. There is no griping, complaining, no resentment. As the body moves to the task it quickly pares away any excess. There is little room for superfluous movement, little space for anger or sorrow. Unhinged from thought the body responds with a more and more elegant motion as physics and biology come into harness: the yoke of Vedic Script , explained Mr. Majumdar, my metaphysics instructor at The New School years ago. Practice this and the mind moves from the specific to the abstract, from the mundane towards the transcendent. Doggone if it doesn’t feel good to boot!

And to art. The parallels to dance are obvious. When I see someone hard at work on a repetitive task I see dance. Trace the movements through time and space, say by a series of lights attached to hands, feet, and hips, and as the patterns become mediated they become drawing, painting, or sculpture. At times the texture of the snow I am moving captures the movement of my shoveling in a similar manner.

Call it work, dance, art, music. Not to get too dewy eyed or spiritual on you, but the doing and viewing of these all seem to collapse into a singularity. Call this the connotative or poetic aspect of language when we speak about it. Call it fun when we do it. For more about dance and language, see Douglass Dunn.

It is not incidental that these repetitive patterns are seen as art. They are inherently pleasing to the senses. As a younger man I loved the way the tractor and plow laid down ordered furrows pitched uphill against erosion. I loved the way the cutter-bar laid down the timothy/alfalfa for the sun to cure, loved the way the hay was pitched into rain-tight stacks or stacked under eaves as bales.

Today I love the way the arrows from my bow trace their way in arcs to find the target, love the way the line from my fly rod pulsates back and forth in graceful and efficient loops. Love the way the hoe moves the earth in the spring, the scythe removes the weeds in the summer, and in the winter the way the shovel moves the snow.

Practical points of shoveling snow:

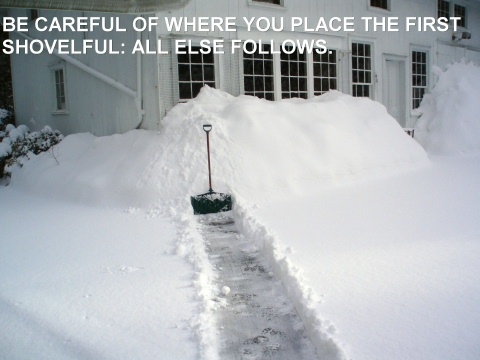

1. Be careful of where you place the first load; all else follows.

2. Always work from a cleared place. Footprints compact the snow, making for jarring interrupted work later. Machines are the worst. They compact the snow under tire and chain, chew up the paving and often require laborious hand removal of hard packed, crude machine placement.

3. Do more, not less than the minimum, and allow the sun to do its part.

4. Practicing on light snow cultivates good habits.

5. Never touch your tongue to a frozen shovel. Keep it firmly in cheek.

All photos except portrait by Bill Bakaits

What an utterly lyrical–and at the same time practical–post. Down here in NYC, I’ve only had occasion to watch as the shopkeepers each try their hand at snow-shoveling technique. Often, they don’t have a chance to get to it before there’s a path of compacted snowy ice. Last year, in the Hudson Valley, when the shoveling sometimes fell to me, it was interesting to think how my Chicago childhood came back: I knew to get out there immediately, while the snow was still powder, no matter what. A useful memory, filed away until needed, much like the memory of typing or riding a bike.

When living in New York I shoveled my driveway often… I never ever had an artistic pattern like that. Must be a virgo who did that.

For your sake I hope it doesn’t keep on coming, no matter how pretty you make it.

Welcome, Patricia, and thanks for the good wishes. Bill says the pattern is automatic with his shoveling method and he may be right ( he’s not a virgo). I just look at the nicely cleared dirveway and count the beauty an exxtra blessing.

Leslie

Hi Patricia,

Well there are different strokes for different conditions: each laying down their own specific patterns. The next to last snow we had, ‘freezing fog’ as described by the weather forecast, laid down like loose sugar and made for the most elegantly smooth sweeps and piles. The last snow ‘ice pellets’ and ‘freezing rain’ quickly formed a two inch crust leading to pronounced jagged cubistic patterns. The slush forecast for next week should resemble fingerpainting.

So we must be at 65 inches and counting about now. The piles against the barn are at the top of the large double doors and onto the topmost of the window panes. As it warms the piles will shrink and then, with a woosh and a crunch the snow and ice on the metal roofs will come down to earth. When this last happened, Leslie’s ‘spare’ Stanza was parked near enough to the eves to suffer its final insult.

But the sun is getting higher, the greenhouse brighter, and that groundhog from Pennsylvania just whistled that spring is right around the corner. Floods too,I betcha!

Well I do wish that I had written something like this, a beautiful essay on shoveling and the joys of snow, rather than to merely have shown pictures. How interesting that your husband enjoys shoveling as does mine. Truly, I thought mine was the only one. I, on the other hand, would be crippled by shoveling (and have been numerous times. Obviously, I am doing something wrong). Here’s to precious few more snow events. I’m eager for maple syrup weather as I still don’t have any and still want to do some baking with it.

Hi, Bill nice funny pictures! The snow looks amazing, we don’t get that here in Georgia. Only get Rain,Heat, and Lightning

Welcome, Pam

It sounds as though we’re better off than we knew, though I must confess a great fondness for peaches and sweet onions, both of which I’m sure do better in your gardens than ours. here’s to a bearable summer!

Leslie